Design Break 03 — Andrea Branzi interview conducted by Francesca Balena Arista

We promise you that we will come back soon to make you dream.

In the meantime we give you pleasant readings on our fabulous world.

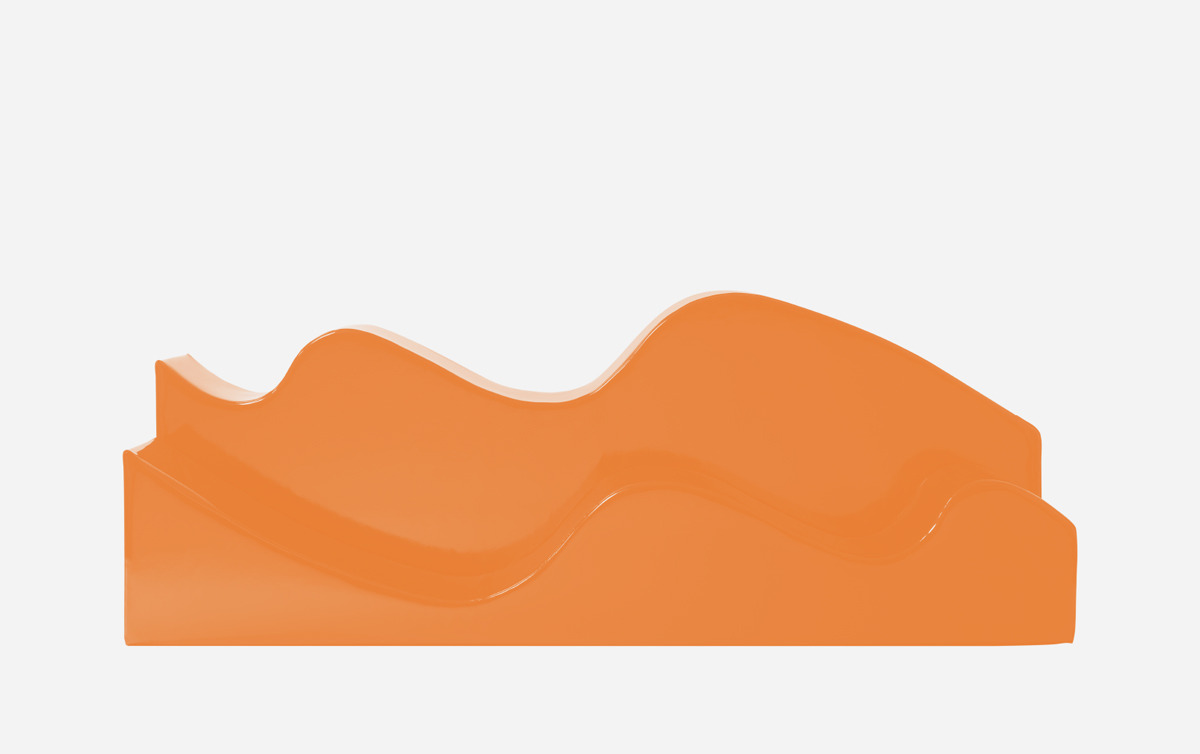

Dear Andrea, if I say Superonda, what comes to your mind?

He smiles

I think of the fact that it was made with hammer blows. The first Superonda, the prototype, was built just the night before the Superarchitettura show was scheduled to take place. Paolo Deganello hammered it into shape until three in the morning.

The countess Gambinossi, owner of the building where our studio in Villa Strozzi was located, was sleeping on the floor above. So at first we were careful to avoid making noise, so as not to wake her up, but at last… I remember Paolo hurling great hammer blows on this wooden Superonda, which had now become a drum… Something really extreme! The prototype was hand painted with wide stripes of lively colors. Then we were driving to the show in Pistoia with our Superonda… Suddenly, a little lorry overtook us, and a sofa in what was the respectable style of those days fell out of it, landing directly onto the road.

If we think of the role an object like Superonda played in demolishing bourgeois living habits, the fall of the sofa is an enlightening image.

Yes, like an omen!

In your book, Una generazione esagerata (An over—the—top generation), you attribute great importance to Super—architettura, as the seminal event for radical design.

Yes, Superarchitettura was a kind of atom bomb, since it really did release a great amount of repressed energy. It was Natalini who invited us to this show, organised in Pistoia in 1966, in an unlikely location called Jolly 2, which was actually a warehouse belonging to a wholesale fish dealer. The manifesto for the show was written by Paolo Deganello (for Archizoom) and Adolfo Natalini (Superstudio had not yet come together).

In historic photos, we see two prototypes of the Superonda couch, which take up nearly all the little room.

Yes. In this improvised show, we exhibited projects which had been especially designed for the occasion. There was a colorful entrance, and then these bright prototypes, made of wood and cardboard. The most explicit thing, immediately grasped by visitors who understood something new and different was happening, was the music of the Rolling Stones, which we used as a sound track for the show. Actually, the music fitted our designs perfectly, as they were pop design. This explains very clearly what our landmarks were — something entirely outside design issues.

And so he did. Cammilli, who was not a traditional industrialist, but had an artist’s education, decided to produce the Superonda. What effect did your furniture have on the audience of those days?

Publication of the Superonda on “Domus”, in an article by Ettore Sottsass, had an immediate effect. Concerning this, I remember a dinner in via San Leonardo with Ettore, Nanda (Fernanda Pivano) and the Florentine painter, Piero Vignozzi, with whom I grew up. We made a panzanella, a Tuscan salad of bread and chopped tomatoes.

The show was inaugurated on December 4, 1966, one month after the Florence flood. The flood was another important inspiration for you, and the wave was certainly a symbol of it.

Arata Isozaki made an important interpretation, connecting the show with the flood…

For the Japanese, great disasters —hurricanes, earthquakes— are part of history; they are not seen as exceptional events, outside of history, as they are for us in the West. Isozaki interpreted the flood as a kind of blank slate, liberating us from the past. The only industrialist who came to see the Superarchitettura show was Sergio Cammilli, the founder of Poltronova who, speaking of Superonda, said: We could try to make it using expanded polyurethane.

You are speaking of the first article about Archizoom published on “Domus” 455, October 1967, written by Ettore.

In fact, as I said, those pictures had an immediate effect. The interiors which appear in the article, with the Superonda, are those of the home of newly wed Cristina and Massimo Morozzi. These are the most famous shots, published in every book, together with those where you of the Archizoom group carry two Superonda couches and set them out on a meadow. The garden that appears in the photo is actually that of Villa Strozzi which I told you about before, where we of Archizoom had our studio.

Both series of photos provide a perfect expression of a new domestic landscape — freer and far from the conformity of the epoch. Regarding this, is there any specific episode you would like to tell us about the Superonda?

Of course. When the Superonda began to be produced, I heard that somebody in Milan had decided to buy it, the only person to do so! I decided to go and meet him. It was 1967. I came to a shop that was all empty and painted white, in Galleria Passarella. A staircase led to the upper floor, and the owner, together with the director of the shop, were sitting on the staircase, in this empty space. It was an enlightening meeting: the owner was Elio Fiorucci. Fiorucci played a key role in renewing taste and culture in Milan. Already in that first meeting, talking to him, I learned some surprising things, the most important one being that you can’t invent fashion, because it exists already. At Archizoom, with Lucia Bartolini, we had made a “dressing design” project, fashion being one of our interests. Fiorucci never called himself a fashion designer — he never designed anything; rather, he called himself a publisher. In fact, he had two buyers who travelled non stop around the world, bringing products, information and items, and not just clothing. His shop had become the hub of a part of Milan which believed in a kind of free—for—all, abolishing the laws of fashion to make way for free individual identity. Just as we used to do in our design projects. In 1975, together with Sottsass, we designed the first Fiorucci shop in New York.

Fiorucci was a great personality. I remember a lecture you gave with Michele De Lucchi, where Fiorucci came to listen to you. He was among the public, in the front seats, and spoke in a very affectionate manner, showing how much he felt part of what was happening. It is nice to know he purchased the first Superonda.

Not only that. It was Fiorucci who suggested we move once and for all from Florence to Milan to manage, as art directors, the new Design Centre for Montefibre of the Montedison group, while he was already directing their fashion design centre.