Design Break 06 — Taking pictures at Poltronova. Cristiano Toraldo di Francia

I was fourteen when I got my first Rondine Ferrania as a present, and started taking pictures with it. The from the negatives I would print them. I quickly realized I could make up for my weak writing skills with a different kind of communication and description of everyday reality. This allowed me to tell stories, probe into the human soul, single-out and make visible moments of life from natural and man-made worlds, which change faster and faster with respect to man’s slow approach to understanding. Then, when I started drawing objects and architecture, photography became the most pertinent and direct communication system to represent and express ways of presence and behavior of a new reality we sought to penetrate by overturning it in our daily routine as bourgeois intellectuals.

Poltronova Backstage.

Poltronova Backstage.

Fortino Editions, 2016.

Curated by Francesca Balena Arista

www.fortinoeditions.com

www.garmentory.com

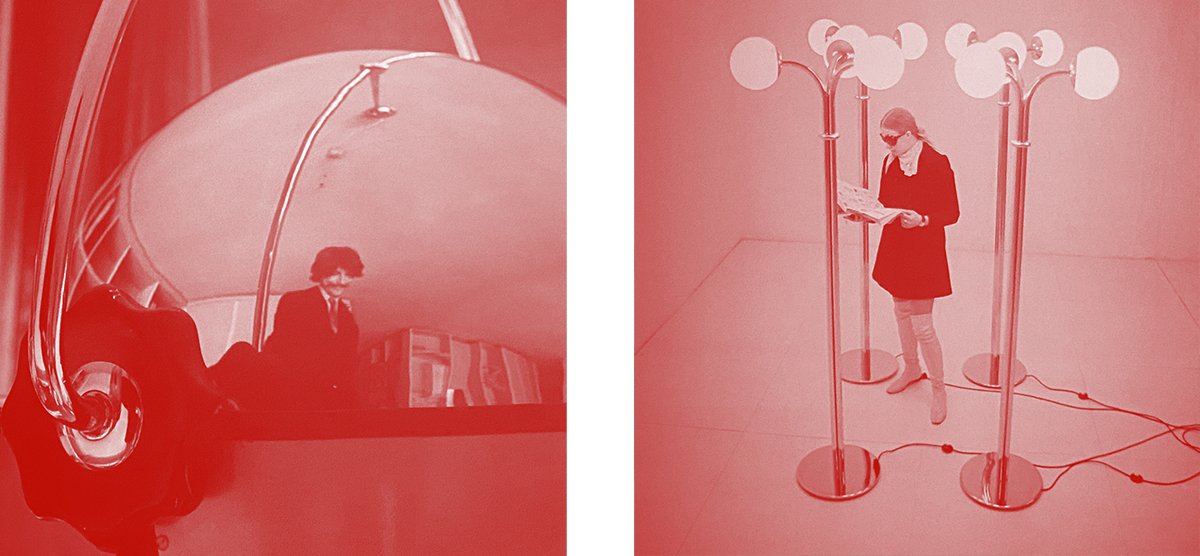

In Poltronova’s impersonal photo studio I built imaginary sets starring Adolfo, Roberto, or myself, immortalized by the picture in a moment of delocalized life, surrounded by objects with a mysterious function. It was important for us as authors to put our physical presence into play by becoming actors/guinea pigs in a representation/experiment that strove to make art and life coincide. I’d take pictures of objects and furniture as if they were the new companions and messengers of a humanity that was changing its habits and points of view, trying to imagine a freer and more creative future. At times I attempted to make them look as if they had a soul and were in close contact with people, while at other times as if they were unmovable obstacles in a rapid stream of ideas and desires.

So I’d take pictures of Luisa Cammilli, a child dressed like a fairy who transformed the Excelsior lamps into a luminous forest. While an equally young Sandro, with his large dark glasses posed fearfully alongside the Gherpe prototype, of which he had just unconsciously given us its name. Soon afterwards, the children, Tina, and myself would make up the “happy family” that lived in my pictures, lai with Ettore’s Kubirolo system cubes to create ziggurats and other mythical shapes.

I remember a photograph where Sergio Cammilli was looking ’somewhat amazed and amused, as if he were in a theater] at the set I had arranged to photograph Sottsass’s colorful ceramic columns, with Adolfo, Cervini’s very young nephews, and two small boys, all wearing long white lab coats except Natalini who was dressed in his legendary black velvet.

These last pictures were an affectionate tribute to my friendship with Ettore and the passion we shared for photography. Actually, it was almost like an undeclared competition with Sottsass. I must admit, I was jealous of his unattainable Hasselblad and legendary Planar lens. Instead, I had to settle for a heavy Pentacon six made in Russia with a defective sprocket. Luckily, it mounted Zeiss lenses. I also photographed, with the same affection and admiration, some objects by my Archizoom friends, convinced I could make a contribution by recording moments and images of the hard and risky adventure we shared. But soon, the impersonal Poltronova photo studio became too small for me, and I began photographing outdoors, starting with the Sofo, with the desire to do without walls and architecture in an attempt to create situations and settings only with the objects in nature, fields, trees…