We promise you that we will come back soon to make you dream.

In the meantime we give you pleasant readings on our fabulous world.

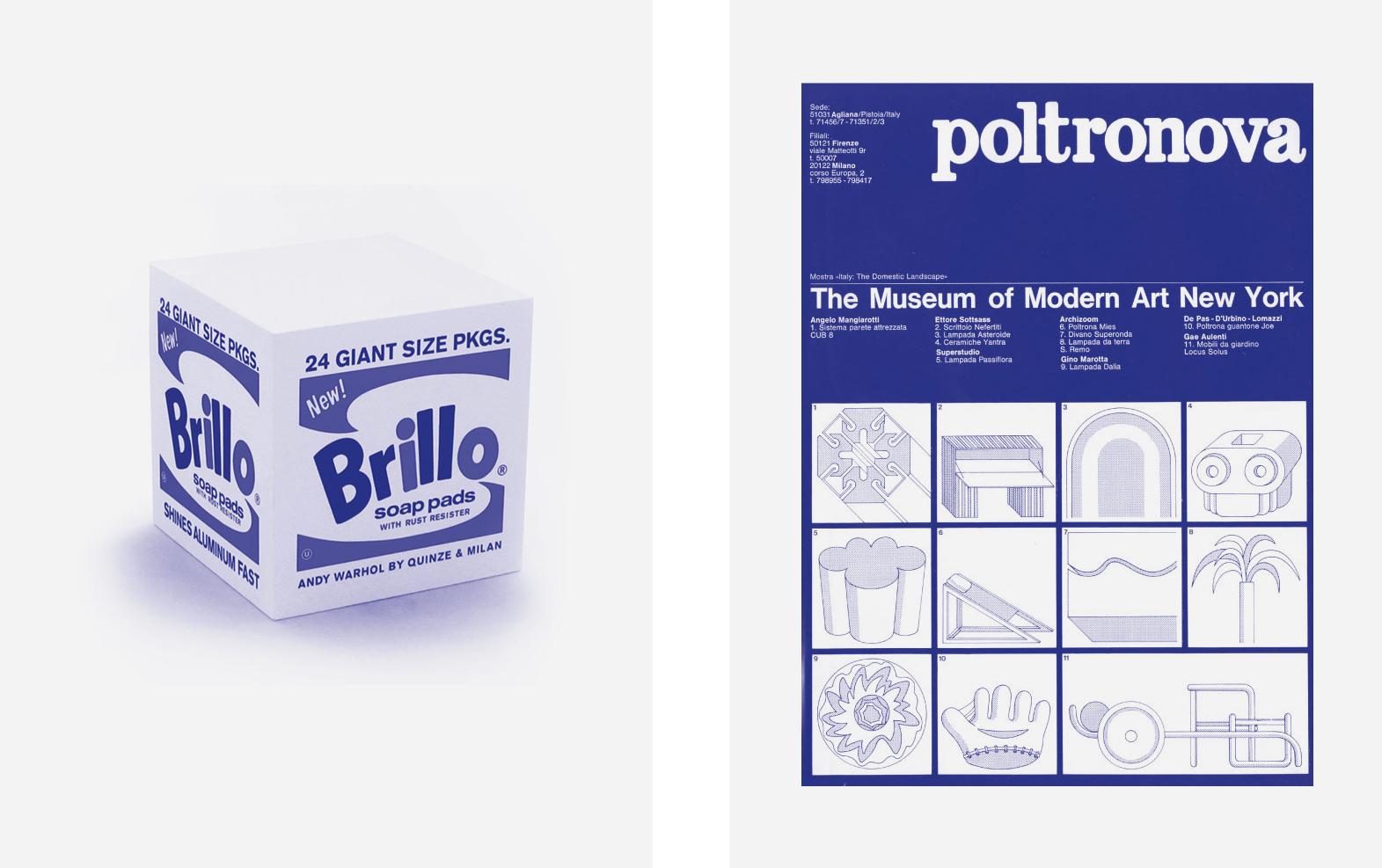

In 1966 Jonathan De Pas (1932—1991), Donato D’Urbino (1935) and Paolo Lomazzi (1936) launched a partnership that has produced extremely interesting projects of urban planning, architecture, exhibit design and interior design over the years. Their output in the 1960s, at the time of the studio’s founding, was already focused on new materials and technologies. Examples include the pneumatic habitat structures for the 14th Milan Triennale in 1968, and the Italian pavilion at the Osaka Expo in 1970, made with modular shelters using inflatable semi—spheres. The same innovative spirit can be seen in the studio’s furniture designs, including Joe (Studio DDL, 1970), a giant baseball glove in soft natural leather, with cowhide lacing, signed by the designers and the manufacturer, and branded with a star, also by the designers.

The 1960s and 1970s were fundamental decades for Italian design and for the industrial companies that produced it: changes took place in both the development model and the materials utilized. The use of polyurethane for seats, sofas and armchairs was a revolution that brought previously unthinkable levels of expressive freedom and experimentation. At the time of its invention Joe was an object that could not be drawn with sufficient precision, so it was necessary to make models in actual size, in clay and plaster, to create the definitive mold in which to inject the polyurethane.

Joe is a hybrid object, not a sofa, but not an individual chair in the traditional sense of the term. It is a sort of “armchair for two”, ambiguous and versatile, with an absolutely innovative form. The objects put into production in the late 1960s and early 1970s by the young designers clearly stood out from those produced by previous generations —even their immediate forebears— because together with the function they combine, or even emphasize, the aspect of “entertainment”, revealing their connection with the youth culture of the time. The years spanning the late 1960s and early 1970s represent a troubled moment in history, and as Andrea Branzi has pointed out the lively creativity of the period must be seen in direct relation to the discontent felt by the younger generations, increasingly bent on expressing their own vision of the world. Regarding the design of those years, Giampiero Bosoni speaks of “monumentalization and destruction of the object”, a definition that is totally apt for the reinterpretation of a baseball glove.

Joe is an extroverted chair, an obviously off—scale exploit, transmuting a garment of sorts into a seat. These are all typical attributes of American Pop Art, which invaded Venice in 1964, marking the introduction of the visual arts in mass communication: not a fashion, but a concrete need for reality. As happened with Joe, Pop Art lifted things directly from the real world, blowing them up and defunctionalizing them to assign them other meanings. The Pop aura of the chair can easily be traced back, both in the physiognomy of the object and the stitching, to the similarly sewn sculptures of Claes Oldenburg.

The tribute to baseball is not just a matter of the form of the glove. The name Joe suggests DiMaggio, the famous star of the New York Yankees, married to Marilyn Monroe, invoked by Simon & Garfunkel in Mrs. Robinson as the last real American hero. This personality was the most pertinent symbol of American mass culture at the time, of the great myths of the collective imagination to which the Italian designers paid homage.

This is a “key” project also for the company, which has kept it constantly in production since 1970. Poltronova was interested in this design trio because “they had made a name for themselves, thanks to their playfully provocative ideas” (Cammilli 1997), and in its new organization Centro Studi Poltronova per il Design has never stopped believing that the aesthetic appeal of the form combined with the idea of a hand that welcomes and protects, like a nest, a cradle, are reason enough to keep the product in the catalogue almost fifty years after its creation.

Joe is one of the most often mentioned and published of all design pieces. Among the many remarks: “it exerts an attraction of a psychic order” (Santini 1977); “it has a life of its own, independent, sensitive, responding to the stimuli of the body that rests there, wrapping it, caressing, triggering thoughts, memories, erotic desires” (Sainotto 1971); it is an “object not without humor, comfortably ergonomic and symbolically alluding to the functional versatility of the various parts of the body” (Annichiarico 2001); it is the “icon of an era” (Pasca 2012).

Joe was presented for the first time at the Salone del Mobile in Milan in 1970, and became a planetary success in 1972 at MoMA New York, in the exhibition curated by Emilio Ambasz, Italy: The New Domestic Landscape, where —as the catalogue explains— it was selected for its “socio—cultural implications”. Since then, Joe has been displayed in the world’s leading museums, receiving prizes and honors not only in its specific sector —design— but also in the world of visual culture in general, such as its insertion in the graphic novel Gea published by Bonelli and created by Luca Enoch. Joe is now part of the permanent collections of the Triennale Design Museum of Milan and MoMA New York. (Elisabetta Trincherini)